Link to previous parts: Part 1 and Part 2

Project Structure within the Company

Let's zoom out further and look at the entire company and other elements involved in actual projects.

Here we're not only considering the departments and how they work together in a single company, but how the company works with the client and other vendors involved in bringing a project to life. Large projects inevitably involve large teams, and decisions made by one team can significantly impact others. The purpose of this section is to look at even larger systems at play, providing insight into the level of influence the Creative Technology team can wield in shaping the outcome of a project. Creative Technology is not merely an isolated group being passed tasks to execute; it is an integral part of a larger team of team, each driven by its own motivations.

Below is a partial list of some of those factors that might drive different teams but often can be diametrically opposed (see also: the good/fast/cheap triangle) :

- User experience

- Ensuring users have a positive and meaningful interaction or experience.

- User engagement/earned media/and “buzz”

- Maximizing reach, shares, and visibility of the project.

- Representing “The Brand”

- Ensuring the final project aligns with the tone and quality expected by and of the client.

- Creative output

- Striving for a high degree of polish and artistry, aiming for innovation.

- Team makeup/staffing/morale

- Assessing capabilities and pushing skill boundaries of a team.

- Use of technology

- Prioritizing seamless, engaging, and reliable technology.

- Timeline

- “It’s Valentine’s day. This project needs to be live for SXSW in March”

- Budget

- Managing financing constraints - often an immovable wall that influences most of the factors above

The push and pull between teams to optimize their goals above are what make projects challenging and fantastic at the same time. While all teams recognize the importance of these factors to some extent, their prioritization of those factors may vary. The tensions are also not often diametrically opposed foes - an increase in one doesn’t often equal a decrease in the other. A superior creative output can come for “free” and feel effortless with the right talent and vision. These can be contrasted with expensive, big budget projects that fail based on poorly conceptualized goals. A longer timeline and bigger budget doesn’t always mean the use of technology will be better or more magical for the user. It’s a complex, multi-dimensional problem, and I would be wary of a company that says they have it all figured out for every project. Internal cohesion and balance within a team are what help stabilize against the external pressures from clients, vendors, and market forces.

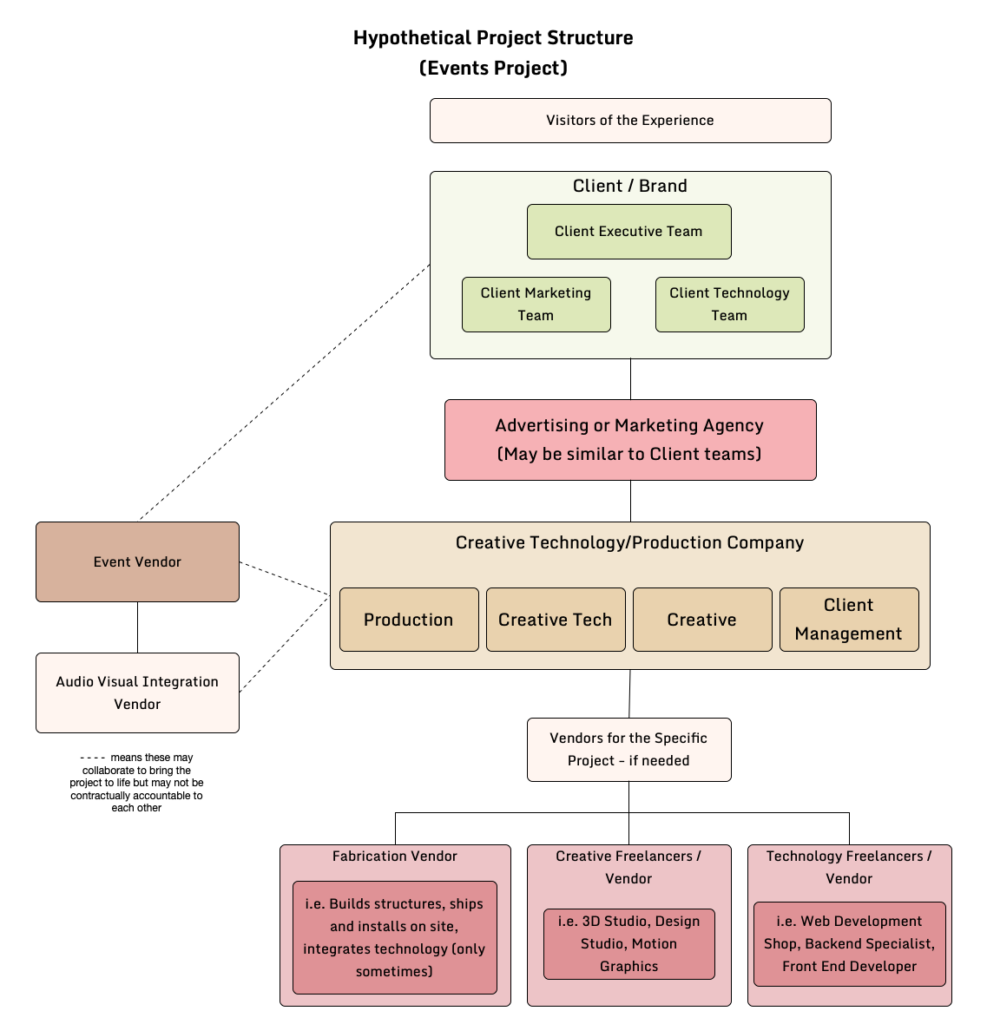

That said - I think it can be helpful to look at these forces not only within the company as in previous parts of this essay, but also in relation to external influences. In the next couple sections, I will show some charts that illustrate how a company and department might find itself within a project. These charts are drastically oversimplified models - we must acknowledge that each project is drastically different. However, they do offer some insight into the diverse decision-making processes within departments and companies, particularly in the context of short and long-term projects.

Agency and Production Company

To begin, we’ll look at a typical structure I’ve often encountered in fast-paced projects, typically associated with large or medium sized events such as booths at CES or pop-ups at SXSW (or something along those lines). It’s important to note that while this structure offers a glimpse into a potential approach, it’s not prescriptive of how things always happen - but just that they could.

In the first chart below, we focus on a scenario where a client or agency collaborates directly with the company or vendor organizing the event. That client may then hire or already work with an agency, and that agency would then hire a production company to execute the idea. For instance, you could frame this as: an automotive brand wants to showcase their new technology at CES using an interactive installation - they use their agency of record to strategize the installation, and the agency hires a production company to actually create it. The automotive brand is just a vendor at CES and is beholden to things like venue and event rules, but still has some sway - they could be considered a peer. Any vendor that the automative brand hires must also abide by these venue and event rules and restrictions ( for example: load in times, access times, power, internet, etc.)

It is worth noting that sometimes the event organizer or the venue itself will also have an established technology integrator that is responsible for installing all of the AV technology for an events space (or there may be a union involved). In those cases, the creative technology agency or production company will have to work directly with that specific AV integrator to make sure that everything is in place to make the event happen. Notably, the power dynamics are a little different if working as collaborative vendors versus a production company that hires and pays their own vendor directly.

Another aspect to consider regarding the chart above is the indicate layers of approval and acceptance within the “Client” category. While communication often occurs directly with client teams that may be involved primarily with marketing/strategy/creative, larger projects may require approvals from higher levels of executives that aren’t as close to the project. That decision making structure can have a lot of trickle down effects for all the parties below if big change or a wrench is thrown towards the end of the project that requires a lot of adjusting.

This communication dynamic is relevant for both event and “permanent” based work. It is crucial to consider how project status is communicated across various levels, the frequency of communication (and reviews), and who oversees the communication flow. Identifying who needs to be informed and involved at each stage is key to maintaining project balance.

Let’s consider a common path of: client makes a request -> sends it to account management -> account management asks production or tech if its possible -> production and tech teams report back on budget and timeline implications to address the change -> change is made (or not made). Sometimes a change is minor and considered within the realm of feasibility/teamwork/overall project vision, and sometimes it is major enough to trigger a considerable adjustment to the project (and budget). Sometimes a request is so obviously outlandish (“Can we have 10 of these instead of 1?”) that it can just stop before flying around to all parties, and sometimes it is less obvious and needs to be vetted (“What visual tweaks can we change on site?”).

Sometimes having more links in the chain (in the case above with the agency between production company and client) can sometimes complicate communication channels. However, experienced folks can recognize this and strive to communicate as clearly as possible so messages get passed along to the right people at the right time.

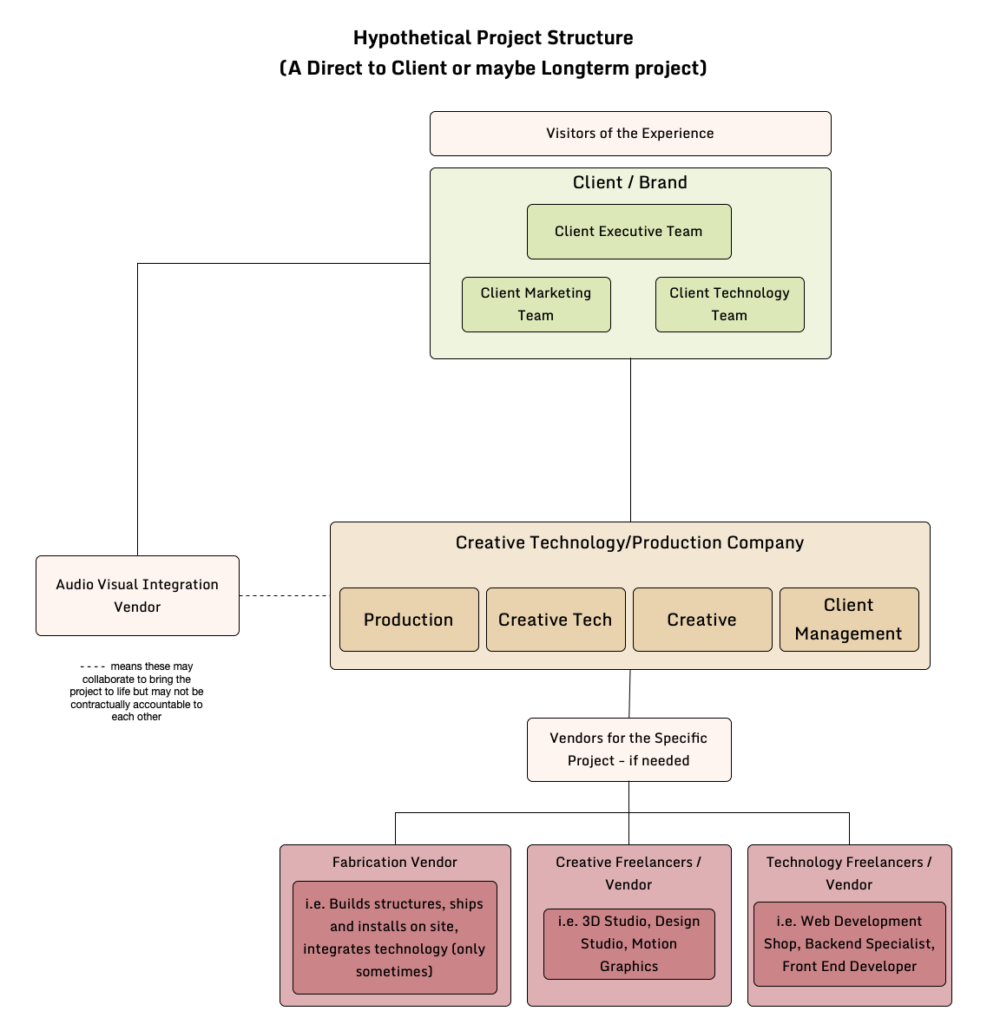

Next we’ll look at both a permanent installation/long timeline project model and one that has a client working directly with a company making the final product.

Direct to Client

Let’s explore another version of this for permanent installations and/or direct to client work. In this model, there is no intermediary agency between the production and the paying customer. To be clear, this removal of a middleman doesn’t mean that communication problems disappear; rather, certain communication challenges just morph into different considerations. This communication might be conceptually the same as the above, but that role of internal guidance of the client is just folded into the project and creative management on the production company’s side.

In this scenario, the agency doing the creative technology work is hired as a sort of "full service" shop, handling all of the aspects of bringing this project to life for the client. This can include project oversight, creative conceptualization, design, fabrication, development, installation, and maintenance, etc. For permanent installations, additional parties may be involved such as the client’s architect of record, the site’s general contractor, or even a content production team responsible for creating visual content.

This direct-to-client configuration is often preferred or seen more often in longer term projects which are typically more extensive (and expensive). Such project may span years and undergo team changes over time. Additionally, there is usually more time allotted for things like discovery phases, design, and production compared to event based projects. These extended phases allow the smaller team more time to deliberate on specific decisions and ensure they are the right ones before moving onto the next large phase.

Questions to consider at this level:

- How do things change as projects scale up or down? How many cooks do you need to make a meal?

- How many reviews or check-ins between teams are too many or too few?

- What does the client's team look like? Do they have a project manager on their side helping to steer the ship or are there multiple stakeholders?

- What is the value of an agency when working on large projects? There may always be a knowledge gap between the client's knowledge and interests and the expertise of the company doing the creative technology work. The layer of translation has to occur somewhere.

- Additionally, for very large branding campaigns that utilize things like print+websites+video content+social media AND experiences, it may not always be feasible or economical for the creative technology company to plan AND build all of that if they also want to focus on "just" creative technology.

- How can you better facilitate communication between a client's marketing team and their technology team?

- Marketing teams can occasionally propose using their own product in a way that it is not designed to be used. The idea they have may not be vetted internally before beginning to work with an external creative technology team. Can you provide a common roadmap for the client on how to quickly arrive at a productive solution?

- Is the value your organization brings to a project more about your creative strengths and ability to problem solve, or is it about some kind of secret sauce cutting edge technology that “only you” know how to wield? What are the costs of always staying at the cutting edge of technology versus working with reliable, tried and true methods?

That wraps up part 3 and generally all I will be covering on company and project structures. In the next part “Creative Technology Ecosystems”, we’ll kind of move on to something that could be it’s own series but in a way feels like part of the continuum of discussing the structures at play with this work. The intent in that section will be to look at where the technologies we use come from and how that can influence our working process.

[…] Link to Part 2 Part 3 […]

[…] Link to Next Part: Part 3 […]